THE ISLAND

Réunion is a small volcanic island in the southwest Indian Ocean to the east of Madagascar, the nearest major landmass. Part of the Mascarene island chain along with politically independent Mauritius and Rodrigues, Réunion formed much the same way as the Hawai’ian Islands in the Pacific, as the Somali plate drifted over a hotspot in the Earth's mantle. Rodrigues is the oldest of the islands, far to the east. Réunion, as the newest, is the only volcanically active island here. As an overseas department of France set between Africa and Asia, Réunion’s unique climatic and geographic characteristics make it uniquely placed as center for agricultural, military, scientific, and tourist activity – elements that make up a large portion of its economy.

My personal experience in Réunion began in July 2013, winter in the southern hemisphere. I was working as an interpreter for industrial greenhouse projects sourced from Taiwan, where I was living at the time, to support the island’s robust, orchid-heavy horticultural sector. During this time, I hiked the island’s calderas, swam in its lagoons, and experienced its extreme weather. Réunion possesses a unique charm that draws visitors from across France, Europe, and beyond, yet faces significant challenges due to its remoteness and numerous natural threats.

Images from my time working as a field interpreter in Réunion from 2013 to 2017. Left: A backhoe lifts the frame of what will become a fully-automated orchid greenhouse into place. Right: Vanda orchids grow hanging in an older greenhouse.

Réunion, a former colony later fully integrated into the French nation-state, is now the farthest outpost of the European Union. It has historically suffered high rates of unemployment, currently over 16 percent (INSEE, n.d.), and reliance on seasonal sectors, which has led to periodic riots (France 24 Observers, 2012) and at times, even calls for independence from France. The French government has promoted tourism, hospitality, and outdoor recreation as a way to build a more robust economy on the island, which has met with success due to the island’s unique topography and tropical climate.

Images from my time in Réunion. Left: Idyllic beaches on the west coast of the island. Right: Natural sites like the famous waterfalls at the Trou de Fer (the Iron Hole) attract tourists from around the world.

In 2023, Réunion hosted 556,089 tourists (around 80 percent from metropolitan France) with an average stay on the island of 18 days, and a total estimated revenue of €477.9 million (Observatoire Régional du Tourisme, 2024), representing an increase of 14.7 percent year on year from 2022. However, the island’s geologic, climatic, and marine characteristics have at times posed a threat to its general appeal as a tourist destination. In this paper, I will explore the impacts of volcanic activity, annual cyclones, and Réunion’s unsettling status as one of the shark attack capitals of the world, using free and open-source environmental data and software to look at surface changes on the island over time.

Overview illustrating the rugged characteristics of Réunion Island, including (clockwise) elevation, hillshade, aspect (slope face orientation) and slope. Methodology: This map layout was made using digital elevation model (DEM) from the SRTM downloader plugin in QGIS, along with Landsat 8 imagery USGS EarthExplorer to compare. Réunion shapefiles related to water and roads were pulled from open-source online databases (Hijmans et al., n.d.).

THE VOLCANOES

The two volcanoes dominating Réunion's landscape add to the thrilling mythology of the island. Piton des Neiges is a large, extinct shield volcano inhabited by rustic agricultural communities of Créole origin, and is a center for outdoor recreational activity. The three craters of this volcano, Cirque de Mafate, Cirque de Cilaos, and Cirque de Salazie, are eroded valleys formed from the slow collapse of the volcanic caldera.

Images of Piton des Neiges (Peak of Snows) from my time in Réunion. Left: The three cirques of the collapsed caldera of the extinct volcano Piton des Neiges, the highest point on the island. Right: Piton des Neiges through the clouds, as seen from my first greenhouse construction site in St-Pierre.

Wher Piton des Neiges is quiet, Piton de la Fournaise is another story entirely, representing what Piton des Neiges may have looked like in its prime. This shield volcano, much like Kīlauea on the big island of Hawai’I, has made its mark as one of the most frequently erupting volcanoes in the world, with oozing expulsions of lava and ash occurring on average twice a year (Chevral et al., 2021). The eruption frequency of Piton de la Fournaise limits human inhabitability of the entire southeast sector of the island, and blocks its use for agricultural purposes. It is, however, a prominent and relatively safe tourist destination in itself, famous for its slow-moving and beautiful lava flows.

Smoking caldera in the crater of Piton de la Fournaise (Peak of the Furnace) during an eruption. Image source: Reuters, 2017.

Eruptions of Piton de la Fournaise. Left image source: Reuters, 2017. Right image source: Île de La Réunion Tourisme. (n.d.).

Due to the volcano's presence, human habitation and infrastructure in the southeast sector of the island is limited to the circum-insular highway system and remote hiking trails. As such, eruptions are not generally life-threatening and the major impacts of its frequent eruptions are restricted to periodic highway damage (Chevral et al., 2021). While highway repair is costly, this level of destruction is likely insufficient to cause significant disruption to the tourism sector. On the contrary, it may even serve to draw tourists to the island. Investigating the potential impact of volcanic activity on the landscape, I performed assessments of land cover and changes in vegetation health before and after two recent eruptions of Piton de la Fournaise.

The map layout above is a normalized burn ratio (NBR) analysis investigating surface changes before and after the January 5, 2002 eruption. These images were taken 1.5 years before (June 2000) and 7 months following (July 2002) this eruption. Visible changes to the barren crater of the volcano (in red) accompany a moderate change in shape of the caldera and change in lava flow path. Finding cloudless imagery is a common challenge in tropical zones. The bright green areas represent cloud interference.

The volcanoes in the Mascarenes are largely basaltic. I used the spectral plot for basalt above, sourced from the USGS Spectral Library (Kokaly et al., 2017), to choose a multispectral band combination that would best highlight vegetation health and basaltic lava flows in the Landsat 8 satellite imagery of the study area. The plot shows basalt's highest reflectance levels at around 0.8 µm (corresponding to Landsat 8 multispectral Band 5 for near-infrared) and 1.2 to 1.8 µm (corresponding to Landsat 8 Band 6 for short-wave infrared). A band combination of R-6 G-5 B-4 gave the best contrast between the barren lava fields and the tropical vegetation.

False-color images with band combinations selected to highlight vegetation and lava flows. Left: Landsat 8 image of Réunion in August 2023 just before the most recent eruption. Right: Landsat 8 image of Réunion in November 2023 following the eruption. The impacts are not readily visible apart from minor shifts in the lava flow path.

THE STORMS

Images from my time in Réunion. Left: Busy marina near Saint-GIlles-les-Bains on the west coast. Right: Boats are hauled ashore for repairs in the coastal city of St-Pierre in the southwest of the island. Cyclones harm Réunion's budding potential as a watersports hub.

Réunion is a rough and rugged place in more ways than one. Beyond its famous volcanic eruptions, intense cyclones frequent the island as a consequence of its location in the tropical western Indian Ocean. Accurate meteorological data sourced from publicly available satellite imagery is a useful tool for government emergency management institutions and general public awareness. Cyclones impact livelihoods — Réunion's reliance on sugarcane production and tourism, and its role as the headquarters of the French military in the Indian Ocean are important considerations in the evaluation of economic resilience and military readiness. To investigate cyclonic impact, I looked at data from two recent storms: Cyclone Iman in March 2021 and Cyclone Garance in February 2025.

Meteorological data from the Sentinel-2 satellite operated by European Space Agency's Copernicus Program was used to produce this animation, showing wind direction and speed during Cyclone Garance in February-March 2025.

Devastation caused by Cyclone Garance in March 2025. Image source: Associated Press, 2025.

When Cyclone Garance made landfall on February 28, 2025, its 200 km per hour winds wrought havoc, causing widespread power outages, prompting civilian evacuations, and leaving at least three dead (Associated Press, 2025). Up to a quarter of the island's population were left without electricity and potable water. A second simultaneous cyclone (see above animation) was just one in a series of powerful tropical storms that devastated another nearby French territory, Mayotte, to the northwest of nearby Madagascar.

Meteorological data from the Sentinel-2 satellite operated by European Space Agency's Copernicus Program was used to produce this animation, showing sea surface temperature change during Cyclone Garance in February-March 2025.

THE LAGOONS

I investigated the potential correlation between cyclonic activity in the western Indian Ocean and another factor that has famously impacted Réunion's attractiveness as a tourist destination. Volcanic islands and their barrier reefs in the Indo-Pacific are a hotbed for marine life, attracting coral-dwelling reef fish and pelagic giants alike. The reef-encircled lagoons surrounding Réunion draw an abundance of large sharks, including tiger and bull sharks, which has resulted in many fatal shark-human interactions in recent decades. These encounters are often gruesome in nature with high-profile headlines like "A tourist went missing while snorkeling. His hand was found inside a shark" attracting negative media attention (Horton, 2019). Poor management of marine recreational activity in Réunion has led to unpopular swim bans, controversial shark culls, and bad publicity impacting the tourism sector.

A tiger shark swims with deceptive laziness along the sea floor off the coast of Réunion. Image credit: Horton, 2019.

The map layout above looks at the marine impact of cyclonic activity in Réunion using a normalized difference water index (NDWI) before and after Cyclone Iman in early March of 2021. Similar to the more familiar normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), commonly used to measure vegetation health, NDWI can be used to look at surface water content by measuring reflective surfaces. Here I used NDWI to reveal changes in the health of Réunion’s lagoons fusing open-source Climate Engine datasets from Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) Terra and Aqua satellite-based sensors from February 2021, around two weeks prior to Iman's landfall, and March 2021, around two weeks immediately following landfall. I used QGIS to produce a change raster, simplified to display “decrease” or “increase” change values for algae and debris. The resulting images show significant lagoon disturbance.

These maps from a recent spatial and environmental study in Marine Policy show shark attack distribution from 1980 to 2017 (Taglione et al., 2019).

Lagoon debris and algae affect surface reflectance and could reveal the impact of the cyclone on lagoons. Lagoon disturbance affects water visibility -- murkiness is known to decrease correct identification of prey items in sharks. Comparing this data to shark attack distributions, we can see that the recreational lagoon areas experiencing the most change after the cyclone have significant overlap areas of known shark attacks (the most popular beach areas are on the northwest coast). More in-depth research is needed, but this could show a link between cyclones and shark attack incidents, impacting Réunion's status as a premier tourist destination.

THE FUTURE

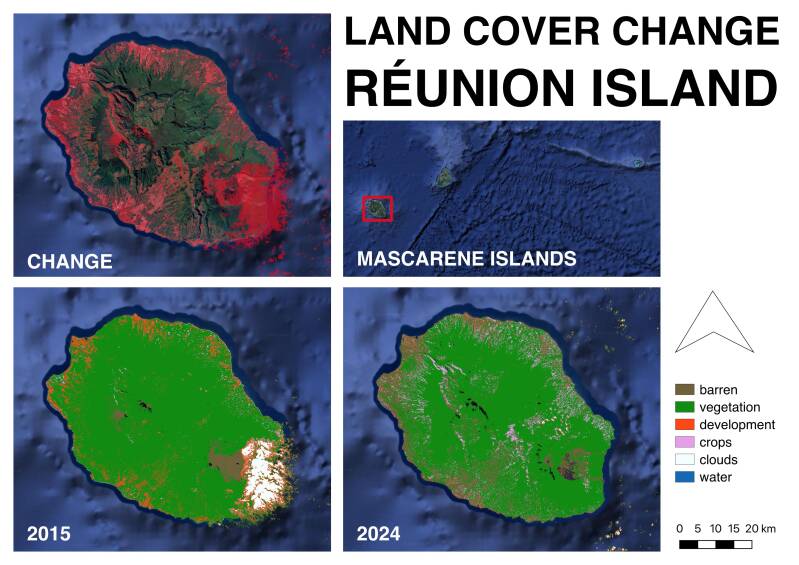

Despite its challenges, Réunion's awe-inspiring geology and rugged landscape provide enough land-based recreational opportunity to weather the storm of its frequent volcanic eruptions, periodic cyclone devastation, and marine predators. Its topography provides a natural barrier to overdevelopment, and we can see from the next map layout that despite some urbanization, Réunion's land cover has remained virtually unchanged over the last decade. I think the future remains bright for Réunion.

Google Earth Engine was used to process these Landsat 8 images, yielding a supervised land cover classification spanning the decade from 2015 to 2024. Despite some moderate change in development in the southwest area of the island around Réunion's second largest city of St-Pierre, the development is less than you might expect for a tropical island with a rapidly growing tourism economy.

REFERENCES

-

Associated Press. (2025, February 28). Cyclone Garance hits French Indian Ocean island of Reunion; police report 3 deaths. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/reunion-island-cyclone-garance-damages-d20ddf429639502e67f97089626bc7ec

-

Carte de la Réunion. (n.d.). Piton de la Fournaise. Retrieved May 12, 2025, from https://www.cartedelareunion.fr/listings/piton-de-la-fournaise/

-

Chevrel, M. O., Favalli, M., Villeneuve, N., Harris, A. J. L., Fornaciai, A., Richter, N., Derrien, A., Boissier, P., Di Muro, A., & Peltier, A. (2021). Lava flow hazard map of Piton de la Fournaise volcano. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 21(9), 2355–2377. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-21-2355-2021

-

Copernicus Climate Change Service. (n.d.). ERA5 hourly data on single levels from 1940 to present [Data set]. Climate Data Store. https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/reanalysis-era5-single-levels

-

France 24 Observers. (2012, February 24). Three nights of riots in Réunion Island: Why “the Cauldron” is boiling over. France 24. https://observers.france24.com/en/20120224-three-nights-riots-reunion-island-cauldron-boiling-over-saint-denis-high-cost-of-living-gas-prices-protest

-

Hijmans, R. J., & Guarino, L. (n.d.). DIVA-GIS: Free spatial data. Retrieved May 12, 2025, from https://diva-gis.org/data.html

-

Horton, A. (2019, November 8). A tourist went missing while snorkeling. His hand was found inside a shark. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/science/2019/11/08/tourist-went-missing-while-snorkeling-his-hand-was-found-inside-shark/

-

Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques (INSEE). (n.d.). Unemployment rates localized by department – La Réunion (series 010751340). Retrieved May 12, 2025, from https://www.insee.fr/en/statistiques/serie/010751340

-

Île de La Réunion Tourisme. (n.d.). Where can you take the best photos of the volcano? Retrieved May 12, 2025, from https://en.reunion.fr/discover/reunion-one-island-seven-ambiances/the-volcano/where-can-you-take-the-best-photos-of-the-volcano/

-

Kokaly, R. F., Clark, R. N., Swayze, G. A., Livo, K. E., Hoefen, T. M., Pearson, N. C., Wise, R. A., Benzel, W. M., Lowers, H. A., Driscoll, R. L., & Klein, A. J. (2017). USGS Spectral Library Version 7. U.S. Geological Survey Data Series 1035, 61 p. https://doi.org/10.3133/ds1035

-

Legros, F. (2015, April 24). Le marché français s'enlise, les marchés européens progressent fortement: Fréquentation touristique 2014. Insee Analyses Réunion, (7). https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/1285788

-

Mongabay. (2024, January 16). Thousands affected as cyclone floods Réunion Island in Indian Ocean. https://news.mongabay.com/short-article/thousands-affected-as-cyclone-floods-reunion-island-in-indian-ocean/

-

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (n.d.). Regional development. Retrieved May 12, 2025, from https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/regional-development.html

-

Prinsloo, A. S., & Fitchett, J. (2024, September 12). Réunion could attract more tourists – study. University of the Witwatersrand. https://www.wits.ac.za/news/latest-news/opinion/2024/2024-09/reunion-could-attract-more-tourists---study.html

-

Reuters. (2017, February 6). The eruption of Piton de la Fournaise. Retrieved May 12, 2025, from https://www.reuters.com/news/picture/the-eruption-of-piton-de-la-fournaise-idUSRTX2ZV8Z/

-

Sennert, S. (Ed.). (2023). Report on Piton de la Fournaise (France). Weekly Volcanic Activity Report, 9 August–15 August 2023. Smithsonian Institution and U.S. Geological Survey.

-

Surfer Magazine. (2011, August 29). Reunion Shark Controversy. Surfer. https://www.surfer.com/news/reunion-shark-controversy

-

Taglioni, F., Guiltat, S., Teurlai, M., Delsaut, M., & Payet, D. (2019). A spatial and environmental analysis of shark attacks on Reunion Island (1980–2017). Marine Policy, 101, 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2018.12.008

About this project

This project is the culmination of a semester's work in open source GIS for environmental research at Johns Hopkins University as part of the Master of Environmental Science and Policy and GIS graduate certificate programs. The maps and environmental imagery here were all produced using open source software and publicly available data provided by NASA, ESA, USGS, and other earth observation institutions.

Create Your Own Website With Webador